How to Teach Kindergarten Students to Write?

How to Teach Kindergarten Students to Write?

What are your opinions on kindergarten writing? Is there an educational approach that has been scientifically validated that we should use? We’ve been attempting to include writing opportunities connected to the whole-group listening comprehension book into the literacy block. Should students sketch in response to the prompt or question before labeling, dictating, or writing? Should teachers teach students how to spell words using phonetic spelling or accurate spelling? Any assistance would be much appreciated.

Kindergartners should, in fact, be writing, and kindergarten instructors should facilitate and teach writing to them.

Unfortunately, there isn’t a lot of scientific study on how to teach beginners to write. Many observational studies exist that offer us an idea of what could be achievable (that is what kinds of instructional routines and environments have successfully existed in at least some kindergartens). There are also a lot of correlational studies that show what could be useful (due to the link between specific early writing abilities and later literacy development in pupils).

However, there aren’t many research that have tried out different writing routines and compared their respective results. That means I can offer some appropriate techniques, activities, and routines — but it’s likely that someone will be able to show that there are better options than what I’m advocating in the coming years.

Writing time and opportunities

It is critical that time be made aside on a daily basis for this type of activity, regardless of how you teach or facilitate early writing. I’ve traditionally expected teachers to dedicate 20-25 percent of language arts time to writing in my framework, and this holds true for kindergarten students as well. In a kindergarten class, because I believe the entire time allotment for language arts should be 2-3 hours, it equals 24-45 minutes of writing time every day.

The remaining time should be used on teaching decoding (e.g., phonological awareness, phonics); oral reading fluency (finger-point reading and choral reading if they are just starting out); reading/listening comprehension; and, maybe, spoken language (e.g., vocabulary, listening comprehension, presentation, conversation).

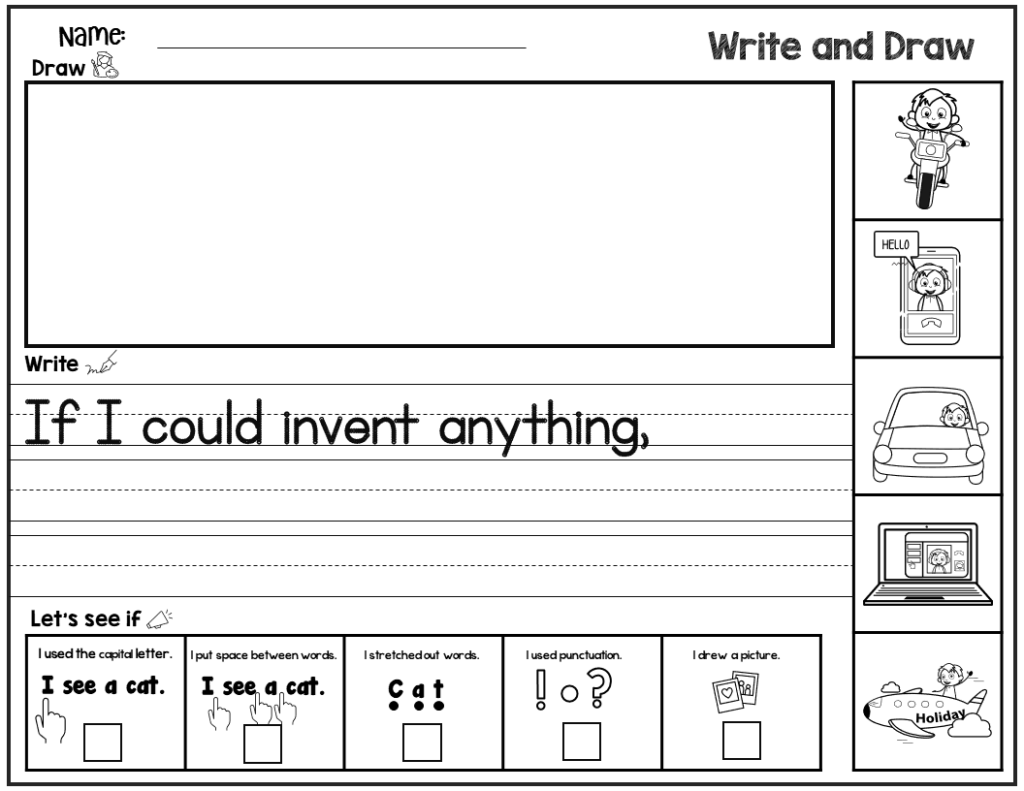

Time spent writing would include not just student writing, but also time spent planning to write (prewriting) and time spent sharing these compositions. Any teaching targeted at improving manuscript/printing abilities or early spelling ability would also be included. But, regardless of what it entails, kindergarten students should be writing almost every day.

Composition of the mouth

I’ve always started kids’ writing with an oral composition. This was true when I was a kindergarten teacher, while I was working with my preschool daughters and grandchildren, and when I’ve consulted in kindergarten classrooms throughout the years.

Oral writing is easier for young children to learn than writing by hand, and it helps them grasp the notion of writing, which soon leads to their developing their own writing by hand.

It’s a shame that the so-called “language-experience approach” (LEA) has gone out of favor.

In a kindergarten, I would typically begin language experiences with the entire class. The first stage is to involve everyone in a shared experience, such as a hands-on activity or an observational event. That may be anything from an art project to a scientific demonstration to a cooking experience.

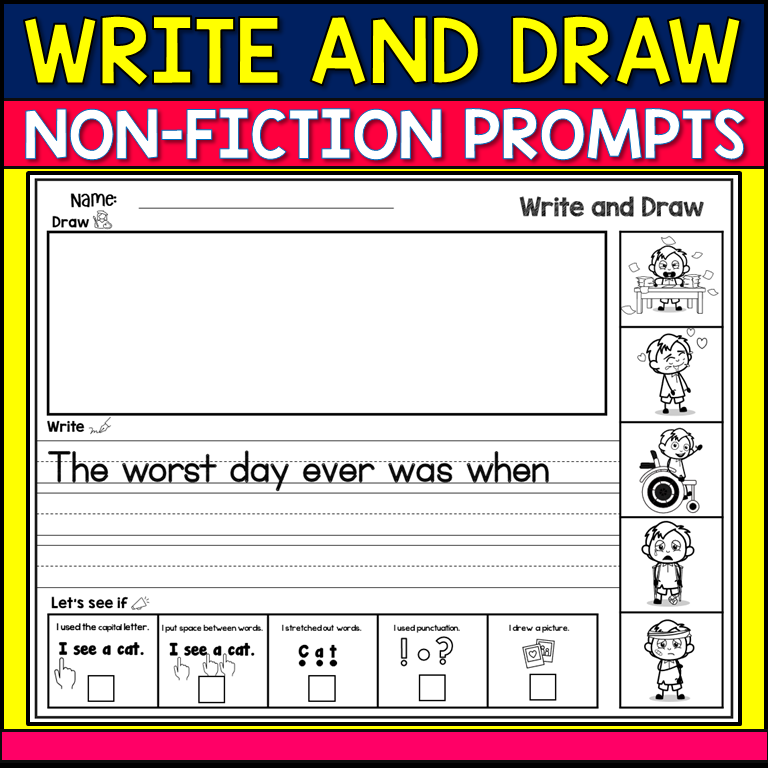

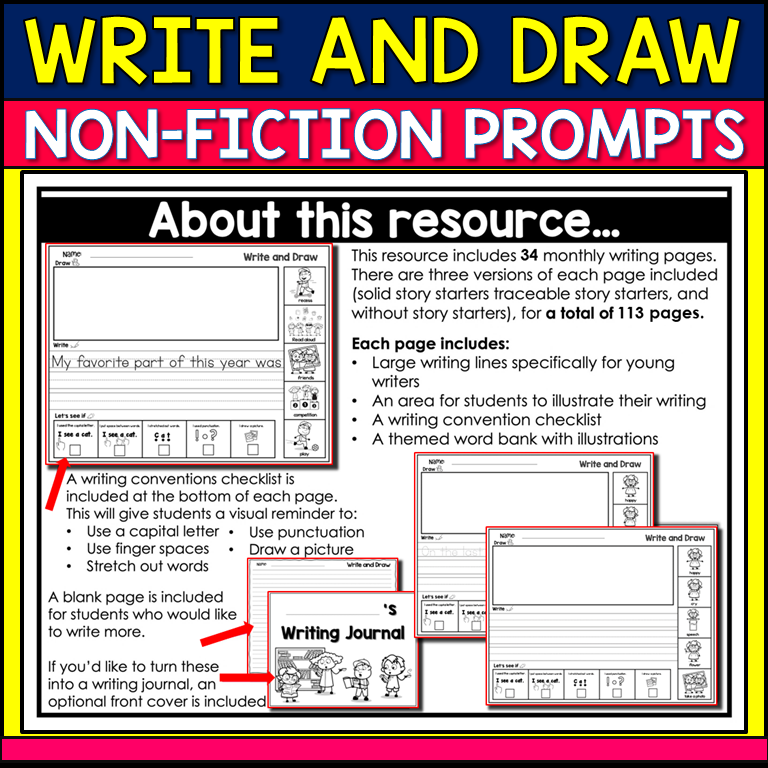

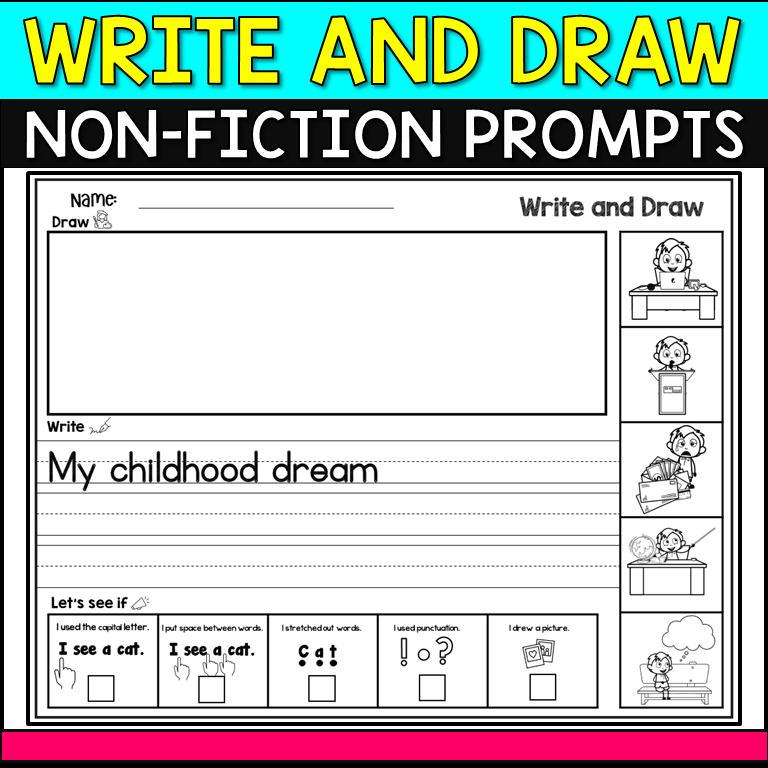

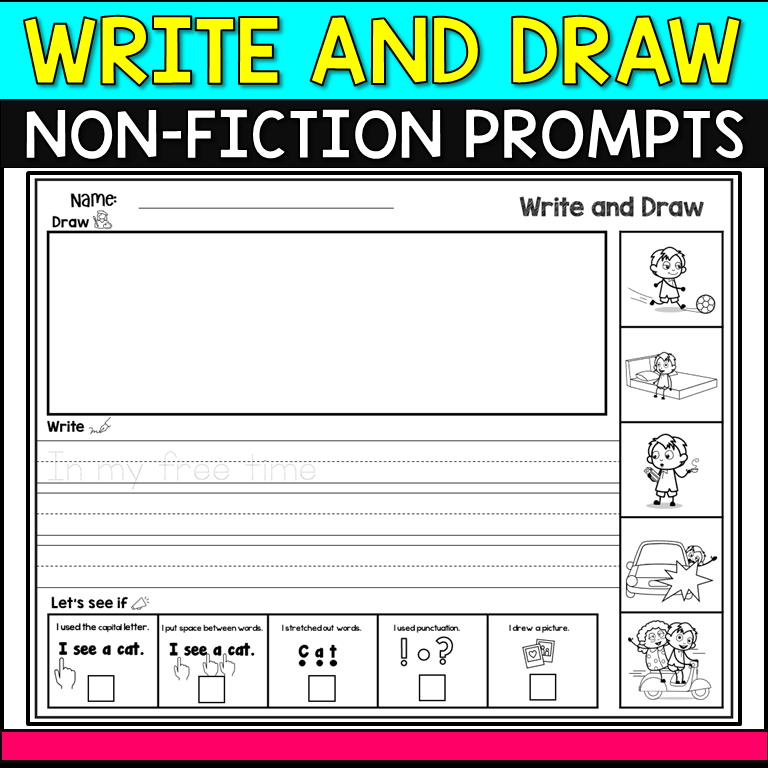

Free Non-Fiction Writing Worksheets For Kindergarten

Then assemble the children around a chart and invite them to share their stories. Encourage them to share about their experiences. Some of this may be “turn and chat,” while others may be students responding to instructor queries individually. The goal is to show children how language helps them to recall and reflect on their experiences.

Tell them you want to write an article about the event now that you’ve had their attention. Inquire about anyone who has something to say about the experience. After that, assist the youngster in constructing a statement about it. This may be as simple as copying what was said, or it could be as complex as assisting the youngster in expanding a notion (S: “Chocolate”). “Was the cake chocolate?” T: S: “It was chocolate cake.”), and then copying it.

To get 4 or 5 phrases, print the kids’ thoughts.

This is something I perform on a regular basis until the pupils can do it on their own.

When they are able, I begin the dictation and transcribing portion of the exercise in small groups or even one-on-one (the experience is still shared by the whole class). Dictation in small groups allows more children to dictate their phrases.

When you’re finished with the language experience technique, the kids should understand the nature of book sentences, how print (the ABCs) is used to record one’s words, and how print goes from left to right and top to bottom. They should also be able to distinguish between visuals and writing.

We frequently make a great deal about providing a positive reading environment in which children have plenty of opportunities to see text and get their hands on books and magazines — both pretending to read and actually reading.

It’s equally as crucial for youngsters to have access to a variety of writing materials. For example, many kindergartens feature a writing area with several types of paper and writing instruments. In my classroom-writing center, I used to have a typewriter (which isn’t such a horrible idea anymore). Because you inquired about naming photographs, providing options for that type of labeling task here seems reasonable.

It’s also logical to include writing components in other classroom centers. You’ll need pencils and order pads if you’re running a classroom restaurant. If you have a classroom post office, you’ll need paper, envelopes, and other supplies. Perhaps my writing center is too dull; perhaps a book publishing firm that allows children to “publish” their work would be more appropriate. Perhaps a sign-making business would be a good fit.

Essentially, the goal is to provide children with numerous opportunities to write.

Act as though you’re writing

When I first begin teaching students to write on their own, I usually start with individuals or small groups (just the opposite of what I did with dictation). You may set two or three kids at a table and give them each a sheet of paper and a pencil or crayon to write with.

After that, I speak with the group about writing something and we discuss their ideas. Similar to the previous LEA tales, but instead of providing a common experience, I’ll ask them questions about what they’re interested in right now in the hopes of getting them to write about their own thoughts.

Sometimes youngsters jump right in and begin writing; other times, they want more assistance to get started. I’ve had kids laugh at me and tell me I’m crazy because they’re only five and can’t write yet.

When this happens, I urge them to act as if they are writing. Those fictitious works range from drawings and scribbles to random letter combinations and real attempts to compose words or make their letter combinations appear like words.

I accept everything.

When a few kids start writing like that — especially if you make a big deal out of it — the other kids are usually eager to attempt it too.

I’m not concerned about stuff like spelling at first. I ask students to spell terms the way they believe they should be spelt.

It may be difficult, if not impossible, to decipher what the youngsters have written at first. I work my way around the group, attempting to transcribe what they’ve written. I generally include a date as well, which may be helpful when revisiting children’s writing folders to see how far they have progressed.

You’re always trying to salt the mine as a teacher. That is, you are always giving them guidance that they would not conceive of on their own. Let’s imagine one of your kids is trying to figure out a spelling using his letter sounds. That’s the type of thing that deserves some media attention. I’d want to bring out to everyone what a brilliant idea it was for young Johnnie or Suzi to use his noises in that way. You’d be shocked how many pupils can suddenly compose words using their sounds.

Once you’ve got a group of youngsters writing like this, the language-experience dictation fades away, and your focus must shift to promoting more genuine writing.

It’s critical to let your parents in on the secret if you decide to do anything like this. Invented spelling, or youngsters trying to spell words based on what they know about letter sounds, is a great way for kids to improve their phonological awareness and develop their decoding abilities. However, some parents may believe that your lack of initial concern about spelling indicates that you either can’t spell or don’t care whether your children can. This isn’t the case, so take care of it now.